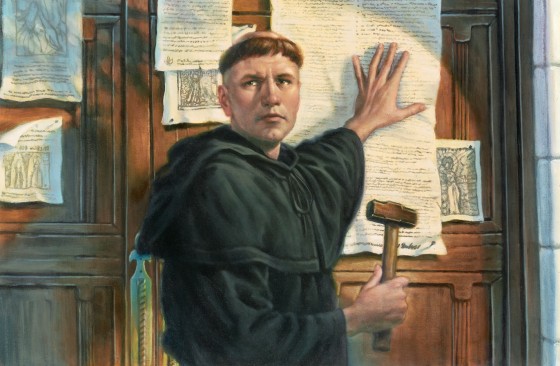

Larry Elliot in his piece ‘Heretics welcome! Economics needs a new Reformation’ reported on Steve Keen and other leading economists ‘nailing’ 33 theses on ‘economic reformation’ to the door of a top university. This was designed to echo the apocryphal story of Luther nailing up his 95 theses 500 years ago. Clearly we do need a reformation, but shouldn’t we remember that Luther was driven primary by his disgust at the corruption inherent in the sale of indulgences?

It was a moral cause, more than an intellectual one. Maybe today’s economic reformation needs to be founded on an understanding of the corruption of the current economic system underpinned by economic ideology such as ‘maximising shareholder value’. Could that light the fire needed, to drive change? Certainly intellectual differences by themselves will are very unlikely to create the popular energy to drive a reformation.

In 1500, Vatican City was in a state of disrepair due to long-running neglect. Catholic finances depended on religious tourism to Rome and who was going to come and see crumbling buildings? The Pope at the time, Leo X, a Medici, decided to renovate them but of course needed money to do it. Selling church offices gave him a start but he needed the top banker at the time, Fugger, to provide much of the financing.

The major push started in 1515 to raise money to fund the building of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

However loans need to be repaid. So apparently Fugger came up with the great idea of selling indulgences – his previous major achievement had been to persuade Leo X that usury or lending was not a sin in the first place. Indulgences meant that parishioners could purchase from their priest a means for themselves or their loved ones to spend less time in purgatory prior to ascending to heaven and the good life. They could buy ‘a stairway to heaven’ and the church could pocket the proceeds.

The major push started in 1515 to raise money to fund the building of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. This was a ‘plenary’ indulgence, the big one that could even get you off the hook for theft and adultery. All other sales of indulgences were banned for 8 years to maximise revenue during this sales spree. Standard sermons (or marketing material!) were sent out around the churchs. Local politicians had even got in on the action by taking a cut of the proceeds. So think on that as you gaze on the beauty of the great Basilica.

Luther called his 95 theses a “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”. As we now know to everyone’s surprise including Luther’s, his 95 learned theses started the disintegration of the Catholic Church. A key element of this was democratisation of religion through ceasing to use Latin to exclude the common people from understanding the bible. If they understood the bible, they would be less likely to be duped by such cons as indulgence sales.

Now we maybe tend to see it as a battle of over theology, but we need to remember it was really a revolt against corruption.

Of course the back lash from the establishment was dramatic as they saw their major revenue stream challenged. Luther when he realised the hot water he was in, tried to row back and claim he was just trying to help the Church see the errors of their ways. It was to no avail. He was eventually ex-communicated and the rest is history.

Now we maybe tend to see it as a battle of over theology, but we need to remember it was really a revolt against corruption. By this, I mean the abuse of power, in this case over ideology, to extract money from the less powerful without providing any commensurate benefits. On the face of it, I would say outrage at being conned is more likely to have given the reformation its drive than technical theological arguments. Who really cared about those beyond the intellectual elite?

So what has this got to do with maximising value for shareholders? This is the seemingly straight forward idea that those employed in businesses should work for the good of those who have risked their capital to set up the business. It was meant to be about motivating managers to do the best for the business rather than feather their own nests. As a result we would have efficient businesses that did the best for all in the best of all possible worlds. That was the economic ideal promoted by such luminaries as Friedman in the 70s.

“Legitimizing this looting of the business corporation is the neoclassical theory of the market economy and its particular “agency theory” application…”

In actual fact, William Lazonick, Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts Lowell, in research funded by the Institute for New Economic Thinking, has shown that this ‘ideal’ has been exploited to extract money from the less well off by the very well off. He writes:

“The corporate proclivity to downsize-and-distribute has become so extreme in the United States that it can now be termed the (largely legal) looting of the business corporation. It bears prime responsibility for extreme concentration of income among the very richest households and the ongoing erosion of middle class employment opportunities. Legitimizing this looting of the business corporation is the neoclassical theory of the market economy and its particular “agency theory” application, with its mantra that, for the sake of economic efficiency, business enterprises should be run to “maximize shareholder value”.”

I would also contend that this has spread cynicism as all that matters is money and (moral) purpose no longer counts. Hence many are writing (e.g. David Pitt-Watson here) on the importance of refinding the purpose of enterprises and particularly banking. This also has an echo of the undermining of motivation to do good by selling indulgence. Why do good if you can buy your way to heaven?

However belief in the need to maximise shareholder value is part of our mental furniture in a similar way to salvation through good works was 500 years ago. So to fight this corruption, we need to help people ‘see’ it is happening. We need to democratise economics and raise awareness of different ways to understand economics, pluralist economics, to allow people to see where economic ideology is being used to con them.

I think that is both why we really need an economic reformation and why it could actually happen. Moral outrage could drive an economic reformation in a way that intellectual differences will probably never do.

Indeed. The outrage that life itself (biosphere within supporting climate) is being commodified effectively through a ‘one-party’ monopoly of economic ‘rationale’ – in the interest of profit-making (profiteering), short-term enough for the material benefit of a few, at the long-term expense of all – dwarfs, in existential terms, the 16th c. aberrations The mainstream ‘orthodoxy’ is hegemonic – dominating academia, business and policy-making – and totally beyond our democratic exercising of political choice. Perhaps Extinction Rebellion is a sign this moral outrage is happening. May our outrage be magnanimous, and wise (not least, in listening to indigenous societies).